As soon as a third-country national or stateless person lodges an application for international protection in one of the Member States, that Member State has to assess which Member State is responsible for examining that application. The ground rule of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) is that Member States have to examine any application for international protection lodged by third-country nationals or stateless persons within the territory of the Member States, and the application will be examined by a single Member State.

The mandatory procedure to determine the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in a Member State is set out in the Dublin III regulation. This procedure describes the criteria that should be applied for deciding which Member State shall examine the application. Such criteria include, for example, whether the applicant has a spouse who has already applied for international protection in a certain Member State. Where no Member State responsible can be designated on the basis of these criteria, the first Member State in which the application for international protection was lodged shall be responsible for examining it.

Practical Guide on information provision in the Dublin procedure

Much of the information which is provided on the Dublin procedure here in the Let's Speak Asylum platform comes from the EUAA Practical Guide on information provision in the Dublin procedure. This guide was created through the EUAA Network of Dublin Units by experts from the national authorities of Germany, Greece, Latvia, Slovenia and Sweden. Valuable input was also provided by the European Commission, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the International Organisation for Migration, the European Council on Refugees and Exiles, Red Cross EU Office, the Danish Refugee Council and METAdrasi. The development was facilitated and coordinated by the EUAA. Before its finalisation, a consultation on the guide was carried out with all Member States through the EUAA Network of Dublin Units.

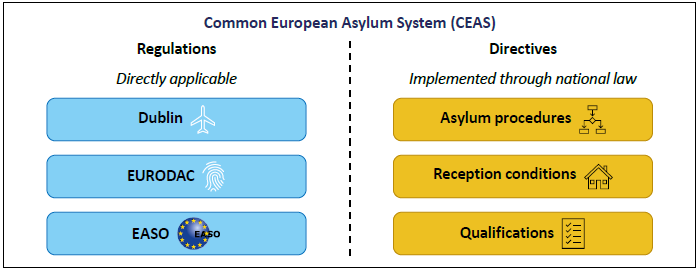

The cornerstone of the CEAS

Each Member State has a responsibility to have procedures in place to provide international protection to third-country nationals and stateless persons in need of such protection. Although this responsibility rests on national authorities, the European Parliament and the Council have agreed on common rules in a series of directives and regulations in order to harmonise procedures and to guarantee high standards of protection throughout the Member States. Together, these directives and regulations are referred to as the CEAS. The Dublin system is the cornerstone of the CEAS and aims at effectively determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection.

The legal framework

The Dublin III regulation (Regulation 604/2013)

The Dublin III regulation is the core of the Dublin system and establishes the Dublin procedure. It contains elements such as the hierarchical criteria to be applied to determine which Member State is responsible for examining an application for international protection, procedural rules as well as the rights and obligations of the applicant in this procedure.

Eurodac II regulation (Regulation 603/2013)

The Eurodac II regulation governs the Eurodac database. Eurodac contains fingerprints of third-country nationals or stateless persons and is used to assist the process of determining which Member State is to be responsible for examining an application for international protection.

Implementing regulation (Commission Regulation 1560/2003 as amended by (EU) No 118/2014)

The implementing regulation contains more detailed provisions for Member States to implement the Dublin III regulation. It also contains the full texts of the common information leaflets designed to explain the Dublin procedure to applicants as well as standard forms to be used by Member States when implementing the Dublin III regulation.

Governing principles of the Dublin system

The Dublin system is based on mutual trust and respect between the Member States. All Member States are under a legal obligation to respect the principle of non-refoulement and are considered as safe countries for third-country nationals and stateless persons.

The principle of non-refoulement under international human rights law prohibits states from expelling, deporting, returning, or otherwise transferring an individual to another country when there are substantial grounds to believe that they are at real risk of being subject to persecution, torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or another serious violation of human rights.

To guarantee effective access to the asylum procedure, Member States have to cooperate with each other to determine the responsible Member State as soon as possible. The cooperation is particularly important where family reunion possibilities are being explored and in cases regarding children to identify family members.

The strict time limits and the clear responsibility criteria set out in the Dublin III regulation serve the purpose of ensuring quick and fair access to the asylum procedure for applicants for international protection. If a Member State fails to meet the time limit to send a request or to reply to a request, or fails to carry out the transfer in time, it becomes responsible for the application for international protection. Since each case is different, every Dublin case must be examined individually, impartially, and objectively.

The EUAA Network of Dublin Units has developed a guidance on the Dublin procedure. The overall objective of this guidance is to support Member States in the implementation of key provisions of the Dublin III regulation to achieve a streamlined application, and therefore to strengthen the CEAS. This document aims to provide guidance on how to operationalise the legal provisions of the Dublin III regulation. This document constitutes a tool to support the Member State authorities in the technical operation of the Dublin Units. This guidance also serves as a self-assessment tool.

To whom does the Dublin system apply

The Dublin III regulation applies to:

third-country nationals or stateless persons who have applied for international protection in one of the Member States.

The Dublin III regulation can apply to:

third-country nationals or stateless persons who are on the territory of a Member State without a residence document but who have previously applied for international protection in another Member State.

The Dublin III regulation does not apply to:

beneficiaries of international protection.

The territorial scope of the Dublin system

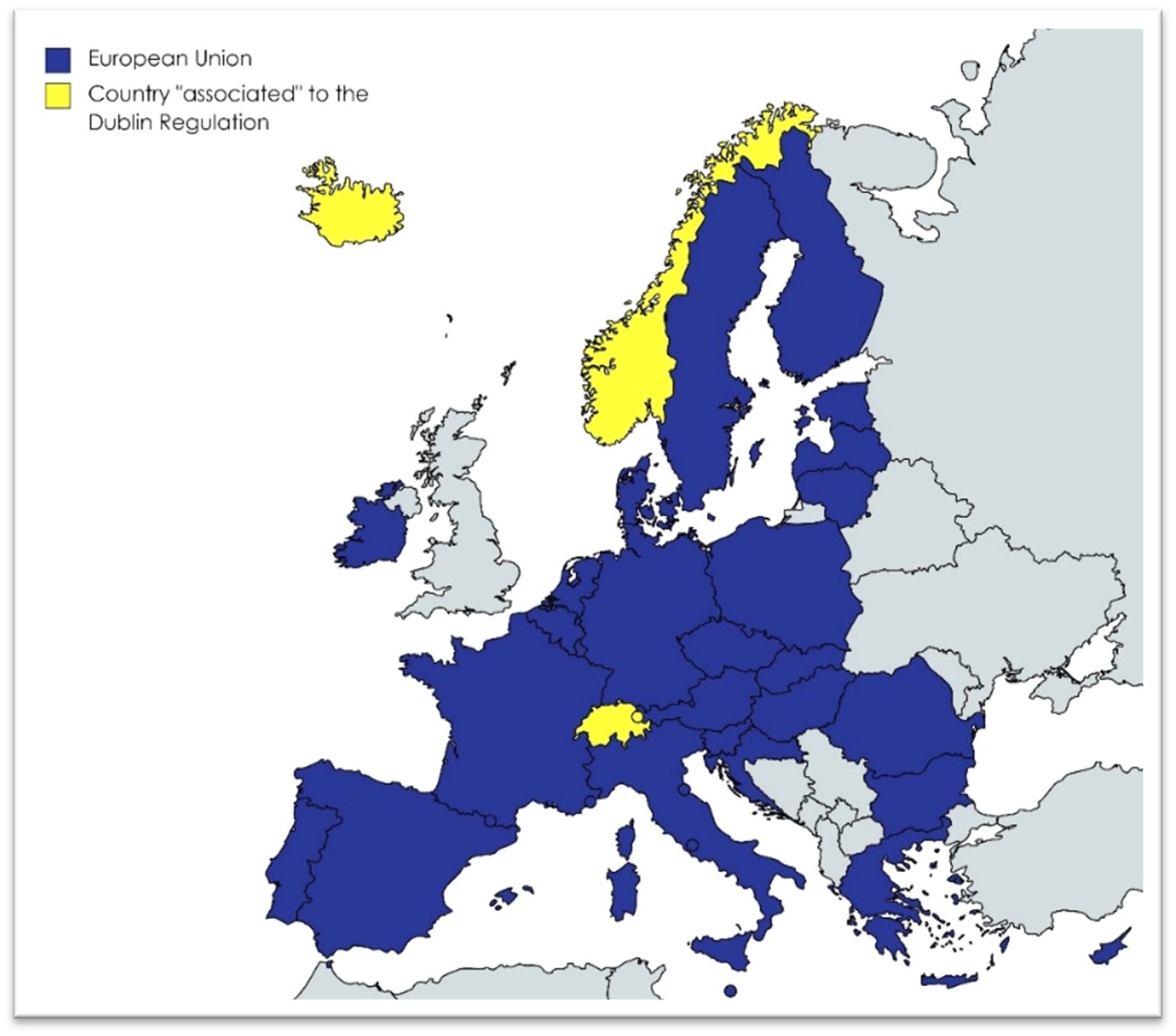

The Dublin system applies to all Member States of the European Union as well as four associated countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) applying the Dublin III regulation.

The criteria used to determine responsibility and their hierarchy

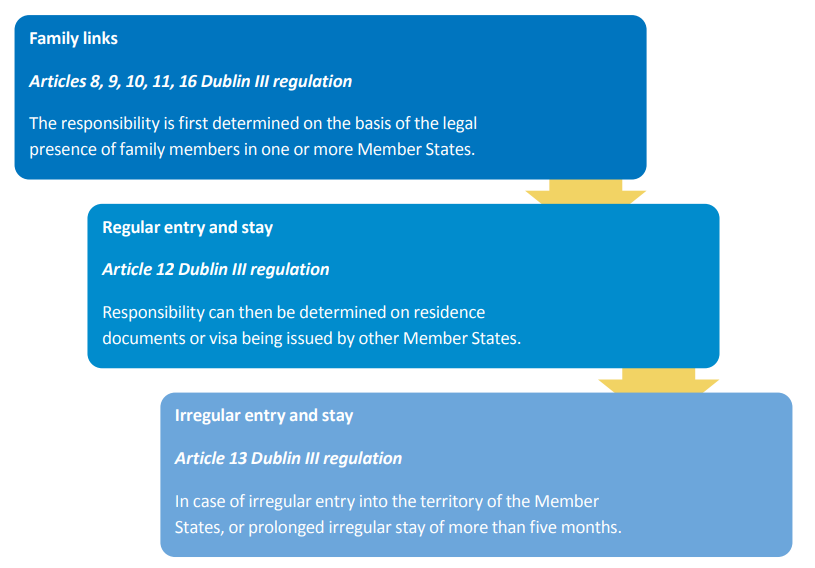

The Dublin III regulation sets out the criteria for determining which Member State is responsible for examining an application for international protection. It is important to explain to the applicant that responsibility can be established on the following grounds:

■ family links;

■ regular entry and stay;

■ irregular entry and stay;

■ previous asylum applications.

These responsibility criteria must be applied in a hierarchical order. This means that family links trump regular entry and stay, and so on.

The responsibility for examining an application for international protection will be determined by the first Member State in which an application for international protection has been lodged. In cases where an application is lodged by the same applicant in a second Member State, that second Member State will generally ask the first Member State to take back the person concerned because the person previously applied for international protection there. In cases where the first Member State established responsibility with another, third Member State, on the basis of the criteria listed above, such as family links or regular entry and stay, the responsibility will generally lie with that third Member State.

It can be challenging to determine which Member State is responsible for the examination of an application, especially if you have no extensive knowledge of the Dublin procedure, or if your work does not usually concern Dublin, e.g. because you work in a reception centre or you conduct registrations.

It is therefore important to remember to properly collect any information you may find that could help determine the Member State responsible. The Dublin Unit in your country will know how to deal with indications that another Member State may be responsible.

Family unity under the Dublin procedure

It is important for the applicant to understand which persons they might be reunited with under the Dublin III regulation, and which persons fall outside of this scope.

■ If the determining Member State considers that another Member State is responsible for the examination of the application for international protection of the applicant, they can send a request to that Member State to take charge of the applicant.

■ The requested Member State needs to accept that they are responsible for the applicant to be reunited with their family members under the Dublin III regulation.

■ It should be clearly explained to applicants that the stronger the proof or circumstantial evidence they can provide to prove family relations and/or dependencies the easier it will be to establish the responsibility of the Member State in question.

■ In cases concerning adult applicants, a written consent of the applicant is required.

■ Cases concerning the family unity of unaccompanied minors should only be facilitated if it is in the best interests of the child, and the determining Member State and the requested Member State should cooperate closely with each other in assessing if family unity is in the child’s best interests.

Dependency and the discretionary clauses

The Dublin III regulation provides some further possibilities for Member States to bring family members or relatives together, or to derogate altogether from the criteria used to determine the responsibility. This concerns the following specific cases.

Dependency (Article 16)

It is possible that applicants depend on the assistance of a child, sibling or parent who is legally resident in a Member State, or vice versa. Member States shall normally keep or bring together the applicant with that child, sibling or parent in case of a pregnancy, a newborn child, serious illness, severe disability or old age. The persons concerned need to express their desire in writing in that case. The Dublin III regulation further requires that the family ties need to have existed in the country of origin already, and that the caregiver is able to provide the assistance needed.

The sovereignty clause (Article 17(1))

A Member State may, at any given time, decide to examine an application for international protection lodged by the applicant in that Member State, even if that Member State is not responsible for the application.

The humanitarian clause (Article 17(2))

A Member State may, at any time before a first decision regarding the substance of an application for international protection is taken, request another Member State to take charge of an applicant in order to bring together any family relations based on humanitarian grounds. These grounds can be based on family or cultural considerations in particular, even where that other Member State is not responsible under the criteria used to determine the responsibility or for reasons of dependency. The persons concerned must express their consent in writing.

Avoiding secondary movements

The term secondary movements refers to journeys undertaken by third-country nationals and stateless persons from one EU+ country to another without the prior consent of national authorities and for the purpose of seeking international protection or illegal stay (in any EU+ country).

It is important to ensure that the applicant understands that only one Member State will be responsible for examining their application for international protection and that there is no freedom of choice on the part of the applicant regarding which Member State this will be.

It is of particular importance in this context that the applicant understands:

■ the hierarchy of the criteria for the determination of responsibility in the Dublin III regulation;

■ the possibilities to reunite with family members through the Dublin III regulation;

■ that all Member States are bound by the rules agreed at EU level or apply similar national rules with regards to the rights of the applicant on things such as accommodation and other basic needs, and also with regards to the obligations of the applicant;

■ the conditions in which the applicants could receive material support in all Member States.

You may want to highlight that:

■ if the applicant engages in secondary movements they could be sent back to another Member State, which could delay their access to the asylum procedure.

Time limits in the Dublin procedure

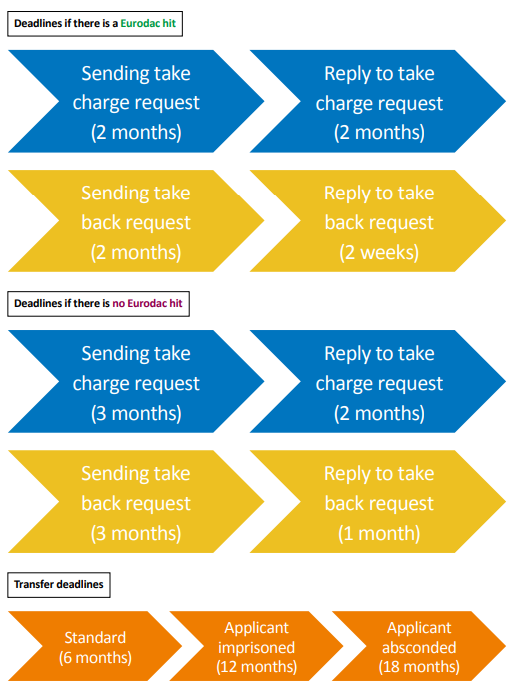

The Dublin III regulation sets out different deadlines for each step of the procedure. It is very important for applicants to know about them, though all deadlines are not equally important to be aware of at all stages of the procedure.

Not knowing when the decision will be issued can cause stress for the applicant. In order to avoid such a situation, it might be useful to explain the deadlines in general mentioned in the regulation. Depending on the case, this could include: the latest point at which a take back/take charge request has to be made to the other Member State, and within which time-limit the requested Member State must answer the request, as well as the time limit for carrying out the transfer. In any case, the applicant must be informed of the time-limit for lodging an appeal or review against the transfer decision once it is notified to them.

Ensuring that applicants are aware of the deadlines that are relevant to their case and giving them realistic expectations on how long different steps in their procedure may take will contribute towards building trust. It should also be noted that to calculate the deadlines correctly the applicant needs to understand not just how long the deadline is but from what point in time it starts. Take your time to explain the relevant deadlines in your Member State.

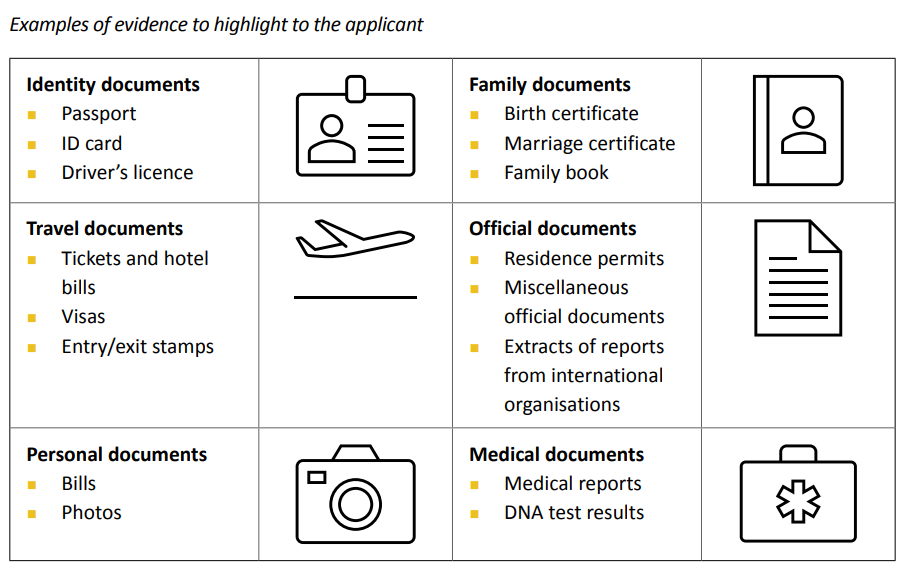

Evidence in the Dublin procedure

It is important that the applicant understands that a Member State that is requested to take charge of their application will request proof or circumstantial evidence to confirm whether it is indeed the responsible Member State. As such, it is important that the applicant provides any elements which can support their claim to the authorities. Giving practical examples to the applicant of what might constitute evidence can help them to better understand what they should provide to the authorities.

It is important to give the essential elements of information on all relevant topics where you might want an applicant to provide evidence. For example, if an applicant is unaware of the dependency criteria they might not think about disclosing the fact that they have a dependent relative. On the other hand, if the applicant clearly states they do not have a dependent relative they will not need detailed information on all the procedural aspects of this part of the procedure.

The Dublin pathway through the footsteps of four fictional characters

The Practical Guide on information provision in the Dublin procedure is accompanied by three fictional applicants and a family of fictional applicants. These fictional applicants will help to illustrate some of the individual considerations that might need to be taken into account with regard to information provision on the Dublin procedure to different applicants. Please note that the examples are not intended to be an exhaustive compilation of all the information to provide but rather to provide some examples of where you might want to focus your information provision efforts. Since procedural steps and organisations continually change, the examples are also not intended to provide exact descriptions of the procedures in use in different Member States.

Below you can see some background information on our fictional characters before you follow them through the steps of the Dublin procedure.